This is the second post in our fifth season of Philly Street Art Interviews! This season is sponsored by Philadelphia International Airport (PHL) and its @PHLAirportArt program, which curates museum-quality art exhibitions that introduce millions of visitors from around the world to the vibrant artistic culture of the region. PHL proudly supports Philly arts and culture/365! Interview and photos by Streets Dept Lead Contributor Eric Dale.

It can be tempting to try and distill artists into a single style or essence. In fact, the social media age has instilled this impetus in most of us. Consciously or not, we’ve been taught that success hinges on presenting consistently identifiable, recognizable, and definable content. So if you’re familiar with Philly street art, you probably think of Carole Loeffler exclusively as a fabric-based installation artist who attaches doilies emblazoned with simple and powerful phrases on them to telephone poles.

But we contain multitudes, and artists perhaps more so than anyone else. Long before she began showing in the street, she was showing in galleries across the country, including in 30 solo exhibitions. She’s worked in rug tufting, cyanotype, collage, quilting, and sewing. But I discovered in preparing for this interview that she primarily identifies as a sculptor!

For most of her career as an artist (she’s also taught art at Arcadia University for 18 years), Carole created abstract sculptural works, primarily from fabric and textiles. She seems to always have had an interest in public communication—one of her sculptures was once displayed in Bella Vista’s Palumbo Park. But the street art, and moreover the text-based pieces, reflected a sudden shift in her approach. In describing the work she displayed at a faculty exhibition in 2018, Arcadia Exhibitions contended that her usage of text left “an impression that the words simply cannot wait.”

Why did the words start to flow from the gallery out onto the street? Read on.

Streets Dept Lead Contributor Eric Dale: Tell me about your relationship with the color red.

Carole Loeffler: The color red… I did a whole sculptural series years ago. For ten years, I made sculpture only with the color red to figure out the color red. I don’t think I ever really did. It was sort of like when you have an itch and you try to scratch it but you still can’t quite get it to go away? That’s the best way I can describe it.

And red has so many connotations that come with it. So red, to me, feels like something comforting and welcoming. I haven’t quite figured it out. I realize sometimes it also looks like yelling when it’s not meant to be—it’s meant to be soothing and soft and welcoming. Why red? I don’t know. Why not blue? Why not yellow? Just red? It’s like an itch. That’s the best way I can describe it. There’s a lot of deeper ways I could describe that—conceptual and all that, but it’s really not that.

SD: So where do you think this interest in a particular color, and the willingness to spend ten years on it, came from?

CL: I think it was—I try really hard to listen to my inner voice, just that ongoing inner dialogue that we all have in our heads. I really try to hone it and listen for the zing. That’s the best way I can describe it. It’s like when you’re making something and there’s this moment where it’s sparkly, or a spark, or it’s like electricity, and it feels right, and it’s good—that. And I kept getting that, so I kept doing it.

SD: What happened that you’re no longer focusing on red anymore?

CL: When Donald Trump was elected in 2016, I just had this urge to make work with text, which I hadn’t really done before. I was always making these abstract sculptures, and I think it was something in relation to Philadelphia not being a sanctuary city anymore. He brought it up at some point, and I was so angry. And I was like I will be anyone’s sanctuary that needs it. I will be your sanctuary.

So I found a piece of vintage bathrobe, and I stitched the word “sanctuary” on it, and that was just this moment of departure. So what I carried from the red, it was this moment of, just, anger and trying to find something to do and respond to. I took the red and I stitched it into something else and then that started a whole different trajectory. I was so angry. I feel like I was always kind of afraid, but I was so angry I kind of didn’t care anymore. Like, I didn’t care to be [indirect] anymore. So that’s why I started using text.

SD: So naturally I mostly want to focus on your street art, because that’s the theme of these interviews, but long before you began creating non-commissioned public installations, you were making these sculptural works, and working in a lot of different mediums all across the country. So can you describe one or two of your favorite projects from your pre-street art era?

CL: Okay. I have a really bad memory—which is a good and a bad thing, because if something happens, I can get over things pretty easily, but at the same time, it’s hard to recall good things. So I don’t really remember, but there’s one piece I did… I would go on long walks with my kids when they were young, and when we first moved to Germantown, and my son was young, I would go on walks around the neighborhood, and I kept finding really beautiful leaves. So I picked up all the different kinds of leaves that I could find, and I traced a silhouette, and I cut them out of felt and backed them in fabric. And the idea was that there was all these different kinds of leaves that make up this neighborhood; all these different kinds of people, and there’s beauty in that diversity.

I love the number 99, because 100 is complete, but 99, there’s always potential for one more. It’s never quite done; it’s never finished. So I cut out 99 different kinds of leaves and strung them up and did an installation with them. And to me, it was like getting to know and embrace and celebrate the neighborhood that I moved to. So I think that was one of the pieces that sticks out to me. And I always keep my work—I don’t keep it, like, hoping there will be a retrospective and I get to show it all—I keep it and then I use it again. So I actually was working on a dress piece last year and took a bunch of those leaves and stitched them into another piece.

SD: You’re going to make it really hard to do a retrospective one day, then!

CL: Yeah, I’m not going to be able to! Because I also throw stuff away and donate it to Goodwill and do funky stuff with it.

I’m trying to think of another piece that sticks [out]. There was another piece that I think was a failure, but I may want to go back to someday. I tried to create basically a little cave that you could sit in. A lot of my work is about comforting or putting people at ease or giving people love, basically, in lots of different ways. So I created this little cave. It actually turned out kind of horribly. I don’t have it; I threw it in the garbage. But do you know when you’re under a willow tree and it just feels so peaceful and calming? And it almost feels like the tree is giving you a hug? I wanted to create that in a sculpture. It didn’t quite work because it was a little too small; the materials weren’t right; but I like that piece and I want to revisit it someday.

SD: So, when Hillary lost the 2016 election, your work suddenly became dominated by text instead of abstraction, which you mentioned. And Arcadia Exhibitions said that this reflected “a new sense of urgency to communicate and to be understood in a more direct way.” Do you agree with that analysis?

CL: Yeah.

SD: Ok. And were you conscious of that transition at the time? Did you know what was going on in your work? Can you just take us back to that moment?

CL: Yeah, I mean, I think I was just… upset. I have these moments that end up being pivotal in my work, and I don’t know that they’re pivotal at the time, but there’s this anxious/antsy/I-gotta-do-something feeling. And that was one of them. I remember just being crushed when she lost—it’s even hard to talk about [now]—and just needing to speak out about it. And so, yeah, I knew at the time that it was going to be a change, but I wasn’t sure I was going to still be doing it now. Something was happening. I wasn’t sure exactly what, but I knew something was happening.

SD: At Streets Dept, we often contemplate the differences between the street art world and the gallery world. And with the artists we cover, it’s almost always a story of beginning in street art and “breaking into” the gallery or fine art world. So I think the fact that you’ve gone from galleries to the streets is very unusual—not that you’re no longer showing in galleries! So I’m wondering how you see this expansion of your practice. Was stepping into street art a part of this election-loss urgency? To connect with more people on more levels?

CL: I think initially it was? The thing that got me into the streets was—I was doing some volunteer work in Kensington with two artist friends of mine, Kathryn Pannepacker and Lisa Kelley, and they would always do this program at a place called Kensington Storefront called Tuesday Tea and Textiles. So you could come in and get a cup of hot tea; iced tea, and you could do something with textiles. And basically, it was the most welcoming space—like the most welcoming place I’ve ever been in all of Philadelphia. You just show up!

It’s no longer open in that capacity now, but I was going every Tuesday for a couple months maybe. But there were regulars—there were people you’d see all the time that would come in. Sometimes people would come in just to have a safe place to sit; even take a nap. Sometimes people would come in and need food. Sometimes people would be really interested in learning how to weave. I remember one day a woman came in and her pants were all ripped, and so I showed her how to mend her pants, and she was so happy.

So there was this one regular—I won’t use his name because he doesn’t know that this whole series started because of him. He’s still around—he’s good; he’s fine—but I just had… It was one of those antsy, anxious, I-gotta-do-something moments, where all these people [are] coming in with stories, and just looking people in the eye and giving them a hug, and there were these really moving moments, and I just felt like it wasn’t enough. Like I wanted to do something else.

So that is when I made the leap from doing gallery work to doing work in the streets. So the first one I ever made was “stay strong,” which I did in 2018. And the idea was that this guy that would always come in… He’s having a bad week, and I was hoping if I made it and put it up somewhere in Kensington, he’d see it, and he’d be like oh! [“Stay strong”] was the thing that he would always say.

So that was the only time I ever used something someone else would say, really. I try to use phrases that are around, or phrases that I would say to myself. Anyway, I love an assignment, being a teacher. I love being in school. So I was like I’m gonna do one every day for the month. I think it was February. Every day I’m gonna put one out. So that’s what it started with. I did “Stay Strong” and I did it for a month, and I was like you know, I’m gonna post them on Instagram because if you don’t live in Philly, you can’t absorb the words, but maybe other people, while they’re scrolling, can have an affirmation that might help them.

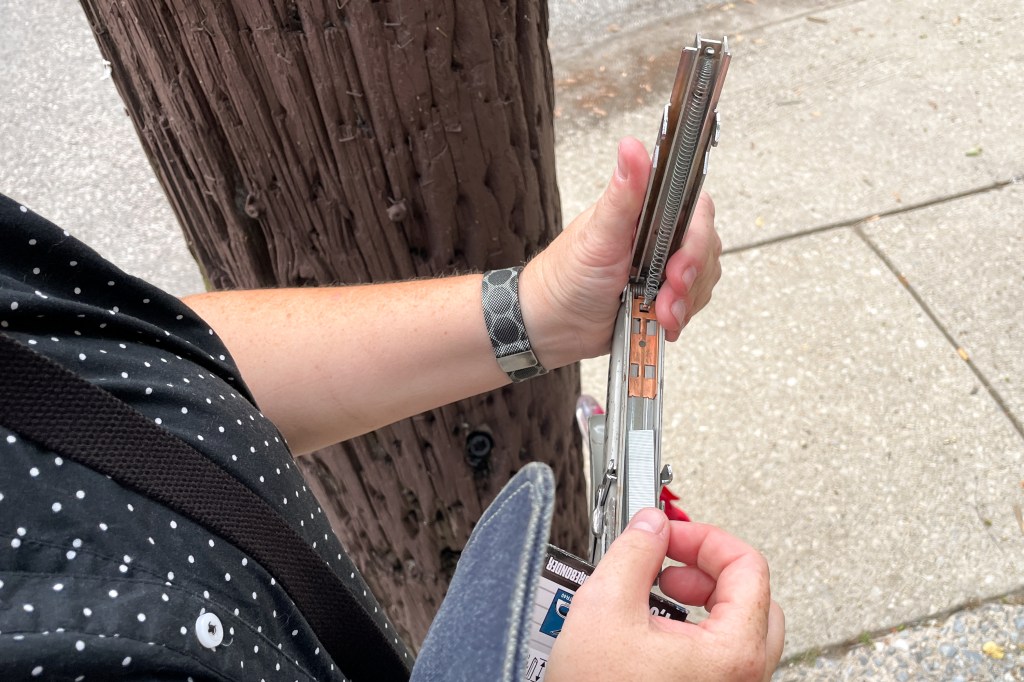

Getting into the streets and putting them out there was like I just wanna offer some kind of comfort to someone. And using a doily, which is the epitome of, like, grandma; some kind of matriarchal figure that makes you feel good and put at ease? That’s the whole [idea]. And then I did it on and off for years.

So that’s kind of how I got into street art stuff. And honestly, I love showing in galleries, but it’s a whole thing. There’s so much structure and politics, [but in the street,] if I just want to put something up, I put something up.

SD: You don’t have to have a bio and an artist statement for street work.

CL: Yeah. And it gets a totally different group of people, you know, which I love about it. And I was anonymous for a long time, but I guess once I started posting on Instagram, people started making connections.

SD: Setting aside the 2016 election and its consequences—if you can—are you happy with how your work evolved because of that moment?

CL: Yeah, I’m grateful for it. I feel like I try not to look back and regret anything. I mean, regret is healthy, I think, sometimes, but… Yeah, I’m happy that it got me to literally use my words. Yeah, I am.

SD: Okay. Speaking of life-altering events, how did the pandemic affect your work?

CL: Oof. So my husband’s a teacher. I was on sabbatical that year, but having three people in school in my house? The fear… Especially in the early times, like, right when it started, the fear definitely affected my work. I’m not sure I made much that was “gallery work” during that time, but I did start posting stuff.

We would take family walks, which—we’re not hiking people; we’re not walking people—but we would start taking family walks together. I did love that about that time, and so what I did was I would have a hanger, and hang a bunch of pieces on the little hangers, and we would all be together, my husband and my kids, and they would help me hang them up. And we hung them up all over the neighborhood. And then I created a scavenger hunt, basically for the neighborhood, so if you found X number of whatever by a certain date… And there are people I’ve never met in person that interacted with that! And they would go out and find them. I made a little hand-drawn map.

So I took this time of just being scared—like, I remember contemplating dying, like, people around you dying—and just tried to comfort people as best I could. And honestly, half of [my work] is for me. It’s comforting for me to see, to cut out, to put down, and then offer to others. So it’s self serving too.

I definitely used that time to also try to model for my kids, because they were scared too. They could feel what was going on—we were wiping off groceries with bleach wipes, you know? So I tried to get out in the streets and offer comfort to other people. And that was sort of the last time I really put a lot out there, besides the airport. I did do like a one-year-anniversary of COVID—I think I [put pieces out] for like a week or something. I love structure, so I think I did it for a week.

SD: Can you tell me about the doilies’ connection to suffragette banners?

CL: Oh my gosh. I love suffragette banners. Just the tradition of banners that are hand-stitched. I love them. Even growing up and going to church, the banners that they have in church that are sewn? It’s one of those zing, unexplainable itch, whatever you want to call it, that I absolutely love. And for me, the love of those banners, the intersection of that, my use of text, and wanting to be more direct, and the fight for women’s voting rights… Like, it’s sort of a trifecta—it all comes together. Bryn Mawr College has a really good archive of suffragette materials; like ephemera and stuff. So I went over there and looked at those—everything I could get my hands on.

And now, sort of looking back, I feel like I’ve started to see the flaws in the suffragette movement, because it was so… Like, they didn’t bring in women of color. They, in some places, didn’t want women of color to be a part of it. So I think initially, I really responded to it and connected with it. But now I’m sort of distancing myself from it because it felt exclusive. It didn’t feel inclusive, the way that you think of it, you know?

SD: Yeah. The way we maybe romanticize it a little bit.

CL: We totally do. That’s with so many things in history, right? Like we romanticize—

SD: …the entire formation of the country.

CL: And then you look back and you’re like no, actually that was awful. When I had a solo exhibition at Arcadia, where I teach, I was really connected to those. Then I started doing more research and I just… I appreciate it, I understand it, but I also see the flaws in that movement and don’t necessarily want to align myself with it so much. So that’s why I opened it up to like, athletic banners, church banners… There’s something for me about the hand stitching, especially people that have long since passed, that there’s this remnant of them in the world still. And I think maybe that’s what I respond mostly to and not as much the politics of all of that. It’s just the humanness of it.

SD: So tell me about this new dress project you’ve been working on.

CL: Okay. I’m making—I don’t know, I sometimes describe it as 100 dresses or 99 dresses.

SD: I was gonna say; 100 dresses?!

CL: I know. And where did this start? I don’t know. But I love a big project. I love an assignment. I love numbers. Just structure and dedication to something. So the idea is that it’s 99 or 100 dresses—that’s undecided right now. The working title is “And So It Goes;” it’s a Billy Joel song. In the song, there’s a part of the lyric that talks about a room, and he talks about this love in this room, and I saw the heart as this vessel to be filled with love.

In every heart there is a room

A sanctuary safe and strong

To heal the wounds from lovers past

Until a new one comes along

—Billy Joel, And So It Goes

It’s sort of corny, but every single dress will have something in and around the heart, and each dress will be a portrait of a woman throughout history. I have one that’s like Gwendolyn Brooks, who was a poet in the 1960s. So I did research on her, found an image of her, found a dress on eBay that looked like a shirt that she had and stitched the entirety of one of her poems on that dress.

So that is Gwendolyn Brooks. There’ll be some that are anonymous, like there’s a piece I made that has golden thread and ink on it. That’s about experiencing miscarriage and that’s anonymous. So there’ll be a number of anonymous women, but then also women throughout history that were sort of groundbreaking. I have three that are gonna be shown at [the upcoming InLiquid show “Voice of the People,” opening on October 18th, 2024]. There’ll be a Jane Goodall dress. And there’ll be a Flannery O’Connor dress.

So, what’s interesting; what’s happening is I’m doing all this research on these women, and [it’s the] same thing that happened with the suffragette banners. The complexity of people—like Flannery O’Connor—like, she was awful. So her quote I stitched—she’s got these flowers on a vintage dress; they almost look like they’re sort of rotten, but they’re still blooming. And there’s this quote that she made about facing your own truth. And you have to stomach it. You have to face your own truths. And so I hope that the project will talk about the complexity of who women have been through history, the good and the bad, and all the in between.

“The truth does not change according to our ability to stomach it.”

—Flannery O’Connor

So it’s a really long-term project. I’ve probably been working on it for three years, and I think I only have like 30-something done. We’ll see, I don’t know if I’ll keep making them. I’m not sure. And alongside that, I do always make text pieces too. So yeah, we’ll see, I don’t know.

Oh, so the plan is: imagine an empty church, or a warehouse, or some big open space, with 99 or 100 dresses hanging from the ceiling, sort of ghostly, and a choir singing a song—they would be singing that song that I started with. That’s the dream. I wrote a couple grants for it and did not get them, but I’m going to keep trying. But that’s the goal. And then I was also thinking about collaborating with friends of mine to do illustrations of each dress and, like, the history of each woman and making little booklets… So we’ll see.

I think I’m at the point in my career where I want to do these big projects and I want to dream bigger. It’s definitely taken me a while. I also think because my kids are older now, I can make bigger things and have more time. But simultaneously, I got fully promoted at my job. So I still have to continue to do research, but I can take four years on a project, and it won’t be counted against me in some way. So I feel like I have this freedom to do these bigger projects.

SD: You’ve stated that the audience for your artwork is primarily women. But in the post I saw where you mentioned that, it seemed like you were really grappling with whether it’s okay to not care how men respond to your work. Is that internal debate still raging?

CL: No, because I don’t even remember it. Haha! See, this is where the terrible memory comes in. I used to obsessively look at the insights and analytics on my Instagram, and I took a look last week for the first time in a really long time, and it’s me, it’s my demographic. Those are the people that buy my work too. On Instagram, it’s usually women from the age of 40 to 60 or something like that. But that’s funny that that’s out there, ‘cause it does not even occur to me anymore. Maybe it should.

SD: Do you find that men and women have different reactions to your work?

CL: I don’t think so. I honestly don’t know what men think of my work, because they don’t talk to me about it.

SD: Well, I mean, that’s kind of your answer right there. So, what was the reaction of the fine art world to your street art?

CL: I don’t think they know.

SD: Wow, how have you kept it from them?

CL: Haha! It’s a secret! It’s so funny because I made a piece this week that said “you have everything you’ve always dreamed of.” ‘Cause when my husband and I first met, we described what we wanted in our lives, [and that’s] what we have now, but I still feel like I’m not a part of the art world. I still feel like I’m not a street artist. I still feel like I’m not where I want to be. But then if I actually look at my resume, I’m like, oh, okay. There’s this weird disconnect, so I feel like I’m sort of quietly working away in my studio, and I feel like Philadelphia, in particular, has no idea what I’m doing. Like, I’m not really part of the Philly art scene at all.

SD: It sounds like you’re at “99.”

CL: Yeah. I don’t know if that’s being a woman and feeling like not enough and that baggage-y stuff. I don’t necessarily care either, in some ways. I do, but I don’t. I mean, I was talking to a friend once and I said something like ugh, I just want to be a successful artist. And she was like what are you talking about? And I don’t remember what it was, but I was like I just really want this thing or this thing. And she’s like do you understand, like, what you’ve done? And I was like yeah, but, you know, not really accepting it. So, I don’t know. I don’t feel like I’m really part of anything.

SD: I’m sorry to hear that.

CL: It’s okay, I don’t feel bad about it. Every once in a while I do. I’ll get a little snarky about the Philadelphia arts scene, but for the most part, I don’t really care.

SD: Okay. And how has the street art world reacted to your gallery work?

CL: I don’t feel like the street art world knows either! I feel like I’m in this little isolated bubble. And maybe people know what I’m doing; I don’t know. I don’t know how they feel about it. I don’t know a lot of street artists, either. I kind of know the ones that are around here… I don’t know.

SD: Why do you think your street art installations are so impactful on people; that people respond to them?

CL: Because I think living is really hard. Like, life is hard. And especially recently, everything feels like it’s been so difficult. And I feel like people need—as cheesy as some of the sayings could be—I mean, they could literally be signs that you could buy at TJ Maxx, that go in people’s houses, like, “live, laugh, love.” Some of them are like that! But people need it. I need it. Every single one that I make are ones that I need. So I assume rightfully or wrongfully that someone else needs to see it or hear it too. I think the world is just so negative and I feel like people need some more comfort. So maybe that’s why.

And the doily [is] sort of the reminiscence of the figures in your life that are comforting to you. I think people like that connection. And I also love the idea of something domestic out in the hardness and harshness of the world. Something soft. To me, my eye goes directly towards it.

Leave a comment