This is the sixth and final post in our fifth season of Philly Street Art Interviews! This season is sponsored by Philadelphia International Airport (PHL) and its @PHLAirportArt program, which curates museum-quality art exhibitions that introduce millions of visitors from around the world to the vibrant artistic culture of the region. PHL proudly supports Philly arts and culture/365! Interview and photos by Streets Dept Lead Contributor Eric Dale.

Perhaps the best thing about Philly’s street art scene is the diversity of mediums that are on view here. Most large cities have murals and graffiti, but not every city has yarnbombers, installation artists, and street art comedians. And only one city has Amy Orr, an artist who has created her own street art medium: the chicken wire-wrapped street sign “totem.”

Made from dozens and dozens of pieces of found ephemera—usually mostly plastic—Amy’s totems have graced street signs outside many cultural hotspots in the city, like the Franklin Institute, Fabric Row, or the Magic Gardens. You may even notice thematic compositions in some of them (the Fabric Row totem was composed entirely of buttons).

Each unique installation is like a little treasure trove, or—depending on how you look at it—a warning sign, inviting you to marvel at or condemn the colorful petroleum products that permeate our existence. But this decade-long street art project is just the tip of Amy’s iceberg-sized career. From galleries and museums to commissions and private collections, Amy has been weaving the detritus of society into horrifyingly beautiful artworks for 45 years.

This is a long one, folks, but it’s worth a read. Amy has such a nuanced perspective on materials, identity, and making it as an artist in Philadelphia. I hope you enjoy our conversation.

Streets Dept Lead Contributor Eric Dale: First, I want to know what to call your street art installations, because I’ve seen you refer to them as “totems,” “surprise poles,” “secret ornaments,” and “alternative graffiti.” So, why so many names and which do you prefer?

Amy Orr: Oh wow, I’m not sure I even remember most of [those names]! I call them “totems;” I call them “installations.” They are little surprises! But I think “totems” is probably a good word for them—urban totems.

SD: Okay, and where does that word come from?

AO: Well, it comes from the idea of a vertical sculpture, where I’m putting things on in a way that you can honor the materials. They’re vertical sculptures that I create in the street, and in the manner of totems, they have one idea on top of another, sort of building up the materials.

SD: I love that! How did you start making these totems?

AO: I really started in street art in my sixties.

SD: That is a non-traditional age to start street art!

AO: That’s right. I had been a college professor for years—I was a tenured professor at Rosemont college, and then continued my teaching career at Tyler and Moore College of Art. And I’ve been inside of an institution for my entire life. I’ve exhibited in museums and galleries. Those options are very limited and they’re not spontaneous.

Looking around me, I realized… I’ve been collecting my materials off the street for my entire life. Looking back on my work, it really has always been about the street. The materials were collections and it was this idea to put the materials back onto the street in a manner that people could appreciate the trash and the street finds and study a little bit of what’s going on in their environment.

SD: That’s awesome—and makes total sense. So, most of your totems honor places of cultural interest or places important to your personal history. Are there any other ways that a place can earn an Amy Orr installation?

AO: Yes! If you ask me, and you want them on your block and appreciate the idea behind them, I will put them up and do projects with you. I’ve done that quite a bit. People want them to be these little spontaneous moments of happiness around the city.

SD: Okay. I might have a request for you then haha!

AO: And also, the street art has really changed its focus over the years, and that has to do with my work in general.

SD: How so?

AO: So I really started working with plastic and found objects at the moment that plastic was emerging. I mean, I’m not quite that old, but it was fantastic! So as I collected these materials in the street… I’m pointing mostly to drug paraphernalia, which is where my street collection started. Because there was so much wonderful plastic: these little inviting containers. They made you want them, you know?

Anyway, it’s really changed completely over time. In the beginning, it was this wonder, the materials—including the drug paraphernalia that I was picking up. They’re wonderful! They’re incredible little plastic forms and sizes. And now, I just… plastic makes me cringe. So it went from being a wonder to being a horror. And so picking it up and organizing it and putting it back on the street is not done with as much reverence. It’s done more in a matter of this is a problem and we need to look at it and take action.

SD: I think it’s very easy to see your totems as a warning sign, almost.

AO: They’re now a warning sign. And I’m beginning to make more that look like warning signs.

SD: How does it feel to now be surrounded in your studio by all of this plastic that you despise?

AO: That’s a good question, because for the last year it’s been in storage. All of these boxes you see, they’re plastic divided by color and size and other things as well. And I really brought them back here—well, because I don’t want to pay for storage and I want the materials in my studio—but to consider whether I want to continue working with it.

Now that I’ve seen my work out in the street for 10 years, it doesn’t all last for 10 years. I mean, some of it is stolen immediately or picked apart, but the one that you posted last year, outside the Magic Gardens, for instance—that one’s been up a long time. I’ve seen them age over 10 years, and when I put plastic out on the street, they start to deteriorate. So I’m causing more of these microplastics underneath my work, and that idea horrifies me, really! So I’m moving more towards preserving them a little bit better before they go onto the street, and that just has to do with sprays. I’m beginning to spray them with layers of acrylic and enamel.

SD: Wow, and that helps with the degradation?

AO: A little bit. And I’m also choosing the plastic more carefully, so that it’s a hardier plastic. I know what will deteriorate and what I shouldn’t have on [the pole] because it’s just gonna fall apart in the sunlight and the weather. The sun really gets to it. But also metal—I’m putting more metal into them, and I’m just being a lot more careful in the materials I do put out there.

SD: And the picking fingers.

AO: Right. It’s funny how some places they get picked and some places they really get left. So I don’t know the complete answer to why those things happen in different places. It probably just has to do with one person.

SD: But even your older works last an incredibly long time. I’m under the impression that you have totems out there that have been up for 10 years, right?

AO: Yes. And then some of them get stolen in a day.

SD: That surprises me!

AO: Yeah. So I have certain rules, [but] that’s part of the game.

SD: Are they being stolen or are they being removed because people consider them an eyesore or something?

AO: Different things. So behind you, the silver one, that is a piece that I put up at the Barnes. [It was] one of my very early ones when I put them up all around the Parkway at all the institutions. The library had actually asked me for one—The Free Library across the street from the Barnes. They had seen them in other places; one of the librarians got in touch with me.

I did put up [one for the library], and I made one for the Barnes at the same time. They were both very elaborate. And [the one at] the Barnes came down within a few days. And I learned a year or two later… A friend of mine happened to be on the board there, and he said he saw it in the director’s office.

SD: What?!

AO: So they had their curators cut it down—carefully, ‘cause, you know, if you’re an artist, you can kind of backtrack and figure out how Amy put it up—though I really do try to bind them up there securely, and I have certain poles I’ll put them on for that reason.

And they’d taken it down, because they want to be in charge of what goes up around their museum. But it’s on a street pole, so they really don’t have jurisdiction over the signposts, which is what I use because I know that they won’t offend most people.

SD: And for it to end up in the curator’s office, though, that means that it was about more than curating their outdoor space, right? It was about—they actually wanted this and valued this.

AO: The fact that she kept it means that they actually valued it. And I was a little pissed off at that. Oh—the other thing that happened simultaneously is there was a Barnes competition where they had an open call for artwork, and I put in a piece. But I did not get into the Barnes show. And at that point I asked for the piece back, ‘cause I knew it was in there and I wanted it. No one else was going to see it. They weren’t going to exhibit it.

SD: I think you have every right to be upset.

AO: They had enough time to get in contact with me. So now it’s a funny story.

SD: Okay, so as far as I can tell, you’ve always created these non-commissioned works in the street using your real name, even when you started in 2013, when street artists were much more concerned about anonymity than they are now. So why was anonymity never an issue for you?

AO: Well, I’m half anonymous in that my name’s not usually on the work. But sometimes it is… and I think I’m going to make a sticker. But I haven’t done that yet. So why wasn’t [anonymity an issue]? Well, I think I always felt a little bit anonymous. It was so much more anonymous than putting work in a gallery—to put it out on the street. Also, it was a little bit provocative, and by using my own name. Oh, I don’t—I wasn’t—

SD: It seems like it just didn’t even cross your mind to be anonymous.

AO: I always felt kind of anonymous doing it. It’s so much more anonymous than the art you do with your name on it.

SD: But your name IS on it.

AO: I do put my name on it, and sometimes I bead my name into it and things like that…

SD: I’m pretty sure that’s how I discovered who was making these things when I was first seeing them!

AO: In the beginning, they really were anonymous without my name on them. And then I became a little bolder about it and thought why shouldn’t my name be on them? I do want them linked back to me. And the reason I got a little bolder about putting my name on it is people were so receptive to it. I think if I was anonymous, it was more because I wasn’t quite sure about what I was doing, and once I became confident, I started linking my name to it.

I realize this is a different subject and you don’t have to get into this… but I could get away with things that other people couldn’t get away with. As an older woman, I could get away with pretty much anything.

Actually, when I was hanging on the Parkway one night, I had the police pull up. And they were just sitting there… And then they turned their lights on… and they were lighting the way for me—they were making sure I was alright. And I realized what a different reception I get. Someone else who looked different than me, who was doing what I was doing, outside the Barnes… They would not have been lighting their way. Even if they were doing the exact same thing.

SD: That’s a great point. So it sounds like the public’s reception to your street art has generally been positive. But I’m curious if the perceived meaning behind your work has shifted along with your relationship to plastic. Are people now saying look at all this plastic—I know she found this on the street—what are we doing to this world?

AO: I think probably, because I do have those conversations. I think they do understand, and I think they have understood from the beginning, the intent of the work.

SD: Where do you think your interest in plastic ephemera comes from?

AO: I have to say my mother. I think my mother really cultivated in me this appreciation of this ready-made ephemera that was coming out of China. It really actually started with, like, Bakelite—just this ephemera, whether it was old fashioned ephemera or new colorful stuff. I just always really had an affinity towards materials and making things with found materials.

I remember, even as a young child, studying the sidewalk as I walked down the street and just looking at the cracks. Part of that was a fear of tripping; I didn’t understand how people could look forward and not trip. I thought you had to look down to make sure you weren’t going to fall. So I just very early on started finding things on the street and wanting to make—to remake them. It’s always been my artistic drive.

SD: Other than picking things up from the street, where do you source your materials?

AO: Oh, that would be it.

SD: That’s it? I thought I’ve seen you request credit cards from people before!

AO: Okay, so the credit cards—yeah, people give me stuff. Now, I mean, people give me bags of stuff. It could be bags of bags. I once picked up 20 years worth of Inquirer bags from the Northeast, for instance. They were all flat and neatly folded.

So people get in touch with me and give me materials. And with the credit cards, they originally started coming from a recycling center. It was a real old-school recycling center in Pottstown, before the cities were doing it. The corks and the credit cards and the plastic bags… everything was divided up as people walked through. And someone alerted me to that and I started getting them en masse.

And also when people see what I’m working on—everyone has collections, particularly the credit cards. Right? Because you probably have a little pile of them that are gift cards and ID cards. And they’re wonderful! And they’re kind of your history! And you don’t know what to do with them. And people mail them to me—piles of cards, and they don’t even cut them up anymore. That’s full of cards [gesturing].

SD: The card catalog? Oh my God—it’s a card catalog.

AO: And these are just the recent ones that I haven’t sorted yet, that keep arriving.

And the first cards I collected when I first started working with them was from my parents when they died. So a lot of the materials start as personal materials, and they have a personal history to them. So they started with these cards of my mother and my father, and of course, being Amy, those were not going to get thrown away. And so neither were the buttons or the letters or whatever else. And so they start with these little collections, and then maybe a small piece of work that then gets bigger and becomes more.

SD: Okay. What is your favorite material to repurpose?

AO: Ooh… Ooh, I have so much. Bones… Bones!

SD: Really?

AO: Bones.

SD: Okay! Where do you get your bones from?

AO: Well, there is a box here full of bones I just found after three years. I was so worried that I lost it. Chicken bones—it’s just like the scraps on the street, so it’s the remnants from meals! So it’s like when I’m finding crack vials; there are chicken bones everywhere—or animal—there are bones really everywhere, along with all of the other stuff. And those are the remnants of the natural world.

SD: Since you brought it up again, it seems like the drug paraphernalia is an important part of your artistic journey. Do you want to talk more about that?

AO: The drug paraphernalia—the continuing drug paraphernalia, which doesn’t stop with the found [crack vials. Much like how my relationship with plastic changed,] in the beginning, they were fascinating, and now…

Here’s drug paraphernalia. [Amy points at an artwork composed largely of orange prescription pill bottles.] This is a piece I did during COVID that never went out. These containers—now they’re making different ones, I think—but they are not recyclable. So the whole pharmaceutical world is making more ways to poison us. It’s horrible, you know, it’s just the tip of the iceberg of what they’re doing to us, right? But I think the reason it appealed to me is they [design the containers] to be very evocative.

SD: The orange bottles?

AO: That’s right—and the drug vials. I happen to have a whole bag of them right here! And they’re just such adorable little things. And they’re all labeled, you know, with different [symbols.] And even the little crack bags, they had little patterns on them. So they all tell stories. They’re kind of a wonder and they’re really evil, all wrapped into one. I find the dichotomy and the juxtaposition of feelings very appealing.

SD: Do you ever find it hard to let go of a particular item to use in an art piece?

AO: Yeah. But then I always put it in anyway. There’s just so much good stuff. Where else should it be if not in art?

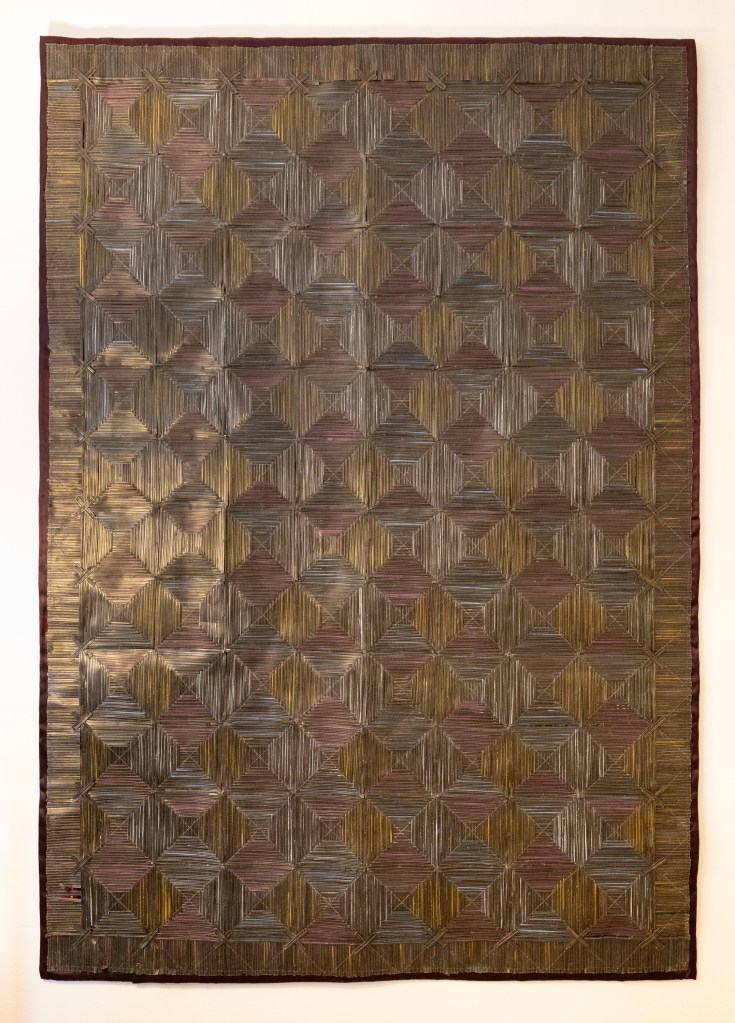

SD: I love that. So I expect that many people would be surprised to learn that you identify as a fiber artist, and that you describe much of your work as quilting. Can you elaborate on how you relate to those terms?

AO: Well, first of all, I think by using those terms, it gives other people a good understanding—a very quick understanding of what I’m doing. I piece things together like a crazy quilt. So I take little scraps that have no value to other people and I put them together to create a wondrous whole. And that is my objective overall: to take these ugly little scraps. And I think that’s the thing about the drug paraphernalia and everything else like it: it’s taking kind of the worst and making it into something really quite appealing and you’re drawn to. And I sew them. Everything is stitched; they’ve got holes and wire and I approach everything much like it was a piece of a scrap of fabric.

SD: And I sort of gathered from doing research to prepare for interviewing you that the world of fiber art is sort of shrinking, or transitioning, or has already gone through a major shift?

AO: Wow. It has gone through so many shifts. There was a moment when fiber art was recognized as the foundation of the arts. I mean, it really is the foundation—think of the woven structure. That’s the basis of everything, whether it’s a canvas or the way people apply paint or…

SD: Wow.

AO: Right? And all the other fields have embraced fibers. I mean, there are sculptors who work with rope—I’m a sculptor, you know? I do consider myself a sculptor with this affinity for textiles and materiality.

SD: Wow. You know, if you asked me what would you consider to be the foundational art form? I would probably say painting—but what are you painting on?

AO: What are you painting on! What are you wearing? The way you’re putting your clothing together?

SD: What is your brush made of?

AO: Yes! You’re handling these, you’re painting on textiles, you’re painting fabric images.

SD: So what is the shift that you’ve seen and why do you think it’s happened?

AO: I’ve seen a shift from fibers being like the underdog—and it has to do with fibers and crafts, but fibers might be the underdog of crafts, who knows—and then to really having an incredible renaissance and people understanding how it’s related to everything. And now I think the other fields have taken fibers in. People aren’t identifying as fiber artists, they’re identifying as sculptors and painters who are approaching materiality much the same way, or using it.

Another reason that I use it as a metaphor for my work is that it’s really very understandable. A lot of people make things with fabric. I mean, almost everyone makes something with fabric, whether they’re sewing, or they’re making one quilt for a baby, or printing a t-shirt, or wearing a t-shirt… But yeah it’s just a really weird field that kind of floats in and out of being respected.

SD: So is it currently in or out?

AO: For me, it’s always currently in.

SD: That’s a great answer. And boy, now I’m even thinking, like, murals in Philadelphia—what do they go up on, mostly? Parachute cloth.

AO: Right. One of my challenges in my life is figuring out how I would translate my work into a mural. I would love to do a mural after doing all this street art.

SD: What would stop you from just filling a whole wall with something like your totems?

AO: I would need to coat it with epoxy resin, and it’s toxic. How to preserve the plastic is a very huge problem. So to do a three-dimensional wall…

SD: …it just wouldn’t have the longevity that you expect from a mural?

AO: Yes. I’m still not clear, technically, how to work it. Plastic is very, very, very problematic—it’s not archival. It could be photographic…

SD: But that feels like it loses something. It loses a lot.

AO: It doesn’t feel right.

SD: Did environmentalism or anti-consumerism play a role in when you first started making these?

AO: Oh, absolutely. It’s very much about consumerism and waste.

SD: How big of a role do those messages play in your work now?

AO: It’s a huge part. Really just the waste and the amount of materials that are being created for really no purpose whatsoever. And for everything we see and I find, there are billions of pre-consumer waste—things that never even make it to the street or to a kid. So for everything that gets made—for every plastic card that you see with a picture, there are thousands that get made that are never used. They just go into the waste stream.

SD: And all of those cut-off corners to get rounded edges. Those are little bits of plastic.

AO: All of it. And they’re all just floating around. They’re just floating.

SD: In the ocean.

AO: Somehow they seem to all make it into the ocean.

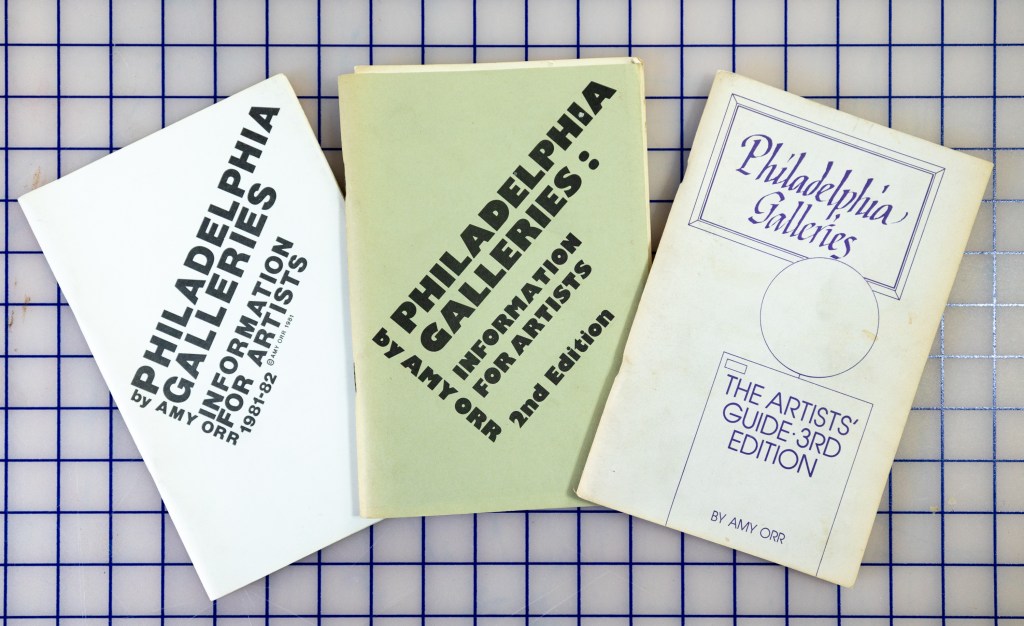

SD: Okay. Let’s shift gears. What was The Artist’s Guide to Philadelphia?

AO: Oh, thank you for remembering that!

SD: Oh, I don’t remember it; I just learned about it while researching you!

AO: Oh my god! So as a young artist—I’m really very shy. I can talk and I can speak in public, but it’s really hard to walk into a gallery and promote your own artwork. And so as an artist out of undergraduate school… How do you know where to take your work? There were actually 50 galleries in the city at that point—and I mean the whole region. So I made going into the galleries a project. I went into every gallery and this became my graduate thesis. I went into every gallery with a questionnaire and I collected information about how they would like artists to approach them and what kind of artwork they were looking for.

SD: That is such a hack for your own art career!

AO: I’m also a real community person. We could collect this information and we could all share the information [as opposed to] one person finds it out and then they just keep it for themselves. And so it was sort of breaking down that wall that was between the artists and the galleries. Many of the galleries were very resistant to talk to me at first, because they didn’t have policies written. They didn’t have anything that was firm.

SD: They’re shooting themselves in the foot, then!

AO: Well, they realized they were shooting themselves in the foot because I would put that information in [The Artist’s Guide.] So in the first edition, you’ll see Roger LaPelle, whose gallery doesn’t exist anymore—he was this character and he would not talk to me. But everyone else really did. And if they didn’t have insurance, they realized they had to get insurance because it was going to be written down they didn’t have insurance, and what kind of insurance. And if they gave everybody different commissions, they had to become more consistent because I was asking them and they had to put it in writing. They probably didn’t have a gallery statement and they had to write a statement about what their gallery was. There was nothing in writing; there was nothing consistent. And I think it also started a lot of collaboration and conversations between the galleries that has led to different things in the city.

SD: And this was your graduate thesis.

AO: That’s right. And then people wanted it, and I started selling them. They were in bookstores all over the city! It was kind of a vehicle for stepping out of myself a little bit.

SD: It’s an ingenious project to accomplish a multitude of things. I love it. So then you continued issuing this after you graduated?

AO: I continued putting it together every year—this was before computers. The final edition I think was actually put onto a computer [but it was too early to be a useful tool]. I was just like I’ve had enough of this. Because it was very laborious, and it was getting very big, you know? We were up to over a hundred entries, or more than that. And I was just tired of it. I have to say that I move on from things.

SD: Well that was my next question—why did you stop publishing it?

AO: I got really busy with other things. Teaching; I had a kid; and doing my own work.

SD: Well this series of guides is one of the many ways that you have connected and mentored and bolstered artists in Philadelphia over the years. So who are or were your mentors and teachers and influences?

AO: A few names that always float to the top of my inspiration list are Joyce Scott, Allison Saar, Nancy Graves, and Warren Muller. All multimedia artists who juxtapose ideas, materials and humor. For the street art, I was really always fascinated by the story of the Philadelphia Wireman. Do you know the Wireman?

SD: No…

AO: The Wireman. One of the gallerists in town found a whole bag, or box, or whatever, and I’m not even sure where, of these excessive, eccentric wire sculptures. And for a while, they were floating around in different shows and things. So certainly that was an early influence on my street art.

But I had fabulous mentors in Philadelphia—teachers. Warren Seelig was one. Teachers at University of the Arts and at Tyler, where I did degrees.

SD: I’ve asked this to two or three guests now: what does it feel like to have University of the Arts closing?

AO: It’s horrible! Philadelphia was such the arts city. And I think that it’s going to continue to be, but, I mean, we are down multiple art colleges. We had the most art colleges in the country, if not the world. At least five, with the different majors, including schools that have art majors and BFA programs that are not necessarily art colleges. I think it’s a very significant difference.

I’m waiting to hear the podcast with all the backstory. It’s not really clear what’s happening. I think it all had to do with real estate, and I think there were people on the board that were in on it and they wanted that real estate on Broad Street. It went down so fast and those buildings are all for sale. It’s unconscionable what happened! It really changes the whole Philadelphia art scene tremendously.

SD: What advice would you give to young artists in Philadelphia?

AO: Oh boy, I think it’s a great time to be an artist, actually. What I do see in the arts in Philadelphia—and I hope this continues—is all the small entrepreneurs that are able to… There’s much more of an appreciation for individual artists; people making things that they can actually sell (something I never did and don’t even understand how to do still). Just being able to create and make their art initiative into products that the vast population will appreciate. I think the art life in Philadelphia is fantastic.

So the advice I would give them is focus and keep building up. This is something I have not done, is to really focus in one area and to continue building that up. I see and I really appreciate people who do that and have been able to do it.

SD: What makes you say you’ve been unfocused?

AO: I don’t know. It feels like I jump around to a lot of different ways of working.

SD: You’ve done something that I think many artists dream of: you quit a full-time job—which, by the way, was a tenured faculty position—to focus on your art. How did you know it was time to do that? What went into that decision and how did you muster the courage?

AO: Ooh, I’m getting nervous just thinking about it! So the first thing is I was able to. I was involved in a lot of other projects that particular year when I decided okay, I’m gonna pull the plug. It’s something we all dream about—it’s not like I hadn’t thought about it for a long time. I was involved creating Fiber Philadelphia. I’m so proud of that. And I think that that directly relates back to putting [The Artist’s Guide to Philadelphia] together; being able to bring the entire city, every single gallery and exhibition space—to understand how they relate to fibers. It was really beautiful.

Early on in Philadelphia—and I think it’s actually important to say this—a family friend said to me when I got out of art college, Amy, you are not gonna make a living in art. I was really pissed at him, but I got it. He said you need real estate. And in West Philadelphia at the time, it was very easy to acquire property. It was very cheap. And so I, as a young artist, did buy three multifamily buildings, and that made a difference in my life. The fact that he said that to me and that I had the nature to do it really changed my life and made it much more flexible.

I don’t have any now; I wasn’t a big landlord, but it really changed my life. So I was always tremendously busy, ‘cause I was also a landlady. And so I was managing buildings, I was doing Fiber Philadelphia, and they were bringing in income. So the first thing is I was able to do it.

SD: How old were you when this was happening?

AO: It was about 2011, so 57. So I wasn’t really young. But I was working at a religious school and I did not want to spend my life at a religious institution. It was very important in my own wellbeing not to be there.

SD: Yikes. So can you just take me back a little bit more? Like, how did you know? What was the moment where you were like I need to do this; I can do this; and here’s how I’m going to proceed?

AO: Absolutely. It was to focus completely. It was one night; I honestly remember this: I woke up in the morning and said I’m leaving. And they didn’t believe me. They gave me a leave of absence for a year! So I had to do it twice. But I left on very good terms. I never regretted it. I never regretted it.

SD: That’s good. Did you ever consider leaving Philadelphia?

AO: Yes, multiple times. I left Philadelphia immediately upon graduating from Girls’ High and moved to Israel. It’s quite a story now, you know. And then for various reasons that had to do with family, I came back. So I was there for about six years, and I came back and just very quickly got involved here.

I kept trying to leave and then things kept me in West Philly. It was having another job here, ‘cause my apartments were here, and the latest thing is my son and his wife have settled down here. And that really surprised me. I thought I’d kind of move to Brooklyn. Oh yeah, I’ve definitely tried, but I really do love Philadelphia.

And I think that West Philadelphia is… the kind of place that people are looking for. It’s extremely integrated with all kinds of people, and always has been. It’s just really mixed, you know? I’m not saying it’s ideal, but at least there are a lot of people who are choosing to live together with a lot of differences. It just feels very right to me.

Leave a comment