Welcome to the Season 3 finale of Streets Dept’s series of street artist interviews created in partnership with Philadelphia’s own unofficial official street art museum, Tattooed Mom. Each month, Streets Dept Contributor Eric Dale will sit down with one local street artist to ask them about their work. Together, we’ll learn more about the incredible artists getting up around Philly. (Photos by Eric Dale.)

Mystery is inherent to street art. Signatures and tags often lead to Instagram accounts where you can follow and support anonymous artists, but for some, mystery and anonymity are a part of the art. No one practices this more staunchly than my interview guest today: the prolific and inventive street artist behind the character known as stikman.

It can be difficult to drop into a conversation about stikman if you’re unfamiliar with the work. It sort of transcends our normal expectations of street art—a property which has definitely contributed to the legendary status of its creator. So rather than getting right into the interview, let’s start with a profile of this famously secretive artist that I assembled while preparing for our conversation. I wanted to delve below the superficial questions one might ask an anonymous artist, so I dug deep into the recesses of the internet to bring myself up to speed.

Before he created stikman, he was “the Stick,” a skinny, bored teenager growing up in suburban Philadelphia. In the 60s, at 14 or 15, he began using a paintbrush and black paint to write his name around town, as well as the word “war” on stop signs. It wasn’t art—it was just what city kids who spent their free time outside did. But even back then, there was evidence of the nascent creative energy that would later fuel his stikman character: he would often construct “gravity towers” out of found materials like sticks and stones.

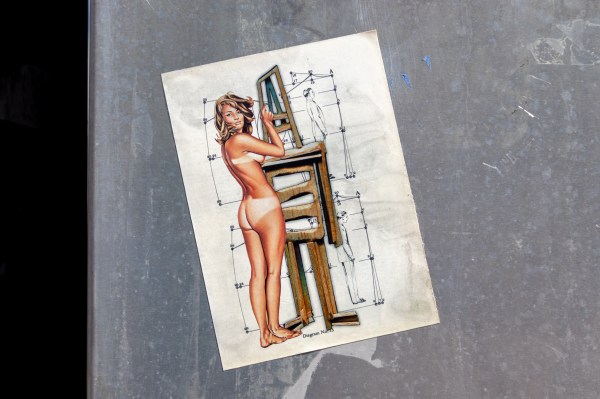

At some point, he developed a fascination with flea markets, and began buying up random objects and gluing them to walls. “I liked the idea that no one could know who was responsible for the shoes stuck on the brick wall or the doll eyes glued onto the breast of the Bikini Babe on a movie poster,” he wrote in 2005.

In 1989 or 1990, an object he discovered at a Philadelphia flea market suddenly changed the direction of his art. 24 inches tall, 10 inches wide, and an inch deep, it was a mysterious plaster mold that bore the impression of a humanoid figure. “It was a stick man,” he said. “However, he wasn’t sticks at all, but what was left after the sticks were gone. I was captured by his presence and absence … I realized as I stared at this plaque that stikman would represent the absence of personality in art. The little being with no stable form. The unknowable consciousness. The disconnect that most viewers of street art feel with the perpetrators of the artwork.”

He eventually incorporated this character, intentionally stylized with lowercase letters and no c, into the sense of mystery he was already spreading on the streets. “My original concept was that the sticks had escaped this piece of plaster and moved out into the world, and now they all are wandering around as a unified force, able to take various shapes and travel wherever he wanted to go,” he said in a previous rare interview. And so stikman was born.

He installed the first stikman, made out of unpainted basswood, in 1992 in Manhattan’s East Village. That first year, he created 50 such men of sticks; about four years later, he began painting his installations and experimenting with stickers.

In the subsequent decades, he has explored a staggering diversity of media: metal, cloth, plastic, glass, stencils, wheatpastes, record covers, playing cards, pages from books—even snow and cigarette butts. He’s probably best recognized, however, for the street tiles he leaves in crosswalks across the country, which are created in the same medium as Toynbee tiles.

Now middle-aged, Stikman feels the passage of time speeding up. Lamenting the fast pace of modern life and 24-hour news, he undertook a ten-year project from 2007 to 2016, which he called The Primordial Cycle. “This has allowed me to slow down my thinking and take a long view of a project instead of my usual manic approach. Each year I produce a new unique figure which I install over and over again during that calendar year.”

For the most part, he’s now back to his classic stick figure design, but as always, his endless experimentation and transformation will continue. “Nothing is planned. Stikman will continue to evolve. It’s all serendipity,” he writes.

And now, my interview with the artist behind stikman:

Streets Dept’s Eric Dale: What do you think is your defining artistic trait? What sets you apart from other artists the most?

The artist behind stikman: I view my artistic practice as improvisational composition with a side order of freedom of expression as well as highlighting an awareness of impermanence and giving the viewer a sense of urgency that we must use every precious moment in life. I try to make small, wordless visual poems for the eyes. I strive to encourage the viewer to see where others may not look. I hope I leave space in my art for people to feel involved and connected and part of the art. Sort of crawl inside and get comfortable with it. Richard Pousette-Dart said “great art leaves half of the creation to the onlooker,” and I believe in that kind of perceptual creativity in my viewers. I’m not sure if that sets me apart from other artists or not. I tend to see myself as related to other artists. I feel like I am part of a large creative system spanning all of mankind.

SD: You rarely sign your work, and you’ve stated that the moniker “stikman” was originally intended only for your understanding. When and why did that name “go public”? What name do you use to refer to yourself as an artist?

The artist: I don’t remember saying the stikman name was intended only for personal use. I have said many times that I liked the way it looked when it was written. The jagged line element that it has seemed to communicate sticks. I remember communicating with Wooster Collective about the name when they were trying to figure out who was putting the little men made of sticks all over NYC. So that was probably when the name went public. I did make a sticker a long time ago that had the name on the bottom of it. I don’t have a specific name to refer to myself. I do say that I am the artist behind stikman when pressed for an answer.

SD: The plaster cast that inspired stikman is such an intriguing object. Have you invented any stories in your own mind about its origin?

The artist: I have mulled over that many times. I have never come up with a satisfactory answer. The mystery is a big element of the fun of it all. I am still scratching my head as to how it was produced. The only clue I have about it is that the person I bought it from told me his brother brought it back from a trip to India.

SD: Why did you go to New York to install your first stikman piece?

The artist: I did not go to New York to specifically install that little man of sticks. I have had a strong relationship with New York all of my life. I have spent time there for my whole life and have done my work there for many years. My first strong memory of the city was when I was five years old. I was there with my family for a day trip and my father stopped for cigarettes at a small shop near the Holland Tunnel and he took me in with him. I walked around the shop and in the back was a chicken in a large cage that had a tic-tac-toe board for a floor. You could put a coin in a slot and the bird then played the game. The details are sketchy to me now, but when I saw that store, I knew I wanted to be part of New York City.

SD: What has kept you so close to Philadelphia throughout the years?

The artist: That’s where I sleep and work and was born. It’s in my blood.

SD: A few people have hypothesized to me that you must have assistants helping you install work; one artist couldn’t possibly be active in as many cities as you have been, the thinking goes. But I’ve also heard people completely repudiate that idea. So, are you just very well-traveled, or do you have helpers?

The artist: I am very well-traveled. I love road trips and walking the streets of cities and towns wherever I go. I work really hard at this enterprise. There are a handful of people who I have entrusted with my work because they have a refined understanding of how I work and had unique opportunities to contribute to the project. That has been very limited—way less than one percent of my work.

SD: In the past, when you’ve been asked about your favorite place to install work, you’ve answered that it was “into people’s minds.” I love that answer, and given the reverence that many artists and fans have for you, I think you’ve been successful in achieving that. What do you think makes stikman and your representations of him so compelling to people?

The artist: I am not sure I have an answer for that. I don’t question the intentions or attraction of the viewers of my work. I am very happy that people have been taking this journey with me and I know the population of viewers has changed a lot over the years. There may be some connection to the lone figure surviving in a rough and tumble world. There may be an attraction to the evolving nature of the work. Maybe just a human attraction to discovery. Maybe they like that I stop a small part of culture from being controlled by the corporate art world. Some people say seeing stikman reminds them that it is fun to be alive.

SD: I’d love to know more about your 10-year project, “The Primordial Cycle.” What was the genesis of that, and what did it accomplish? And how did you approach the creation of those ten designs?

The artist: The ten year cycle was sort of a challenge to myself. I usually work on projects for a duration of a few weeks to a few months. I thought I would find it interesting to use a figure for one year and then use a different one for the next year. I based the imagery on some digital graphics I had been working on. I liked the way that the variations morphed from one to another. I was also listening to some John Cage song cycles and was swept up into that mindset. I did find it very rewarding.

SD: When did you start making street tiles? Were those inspired directly by the Toynbee Tiler?

The artist: I started experimenting with the tarmac figures in 2003. It was a long, slow process of trial and error to figure out exactly what I wanted to do and how to do it. The idea was that the small wooden figures were placed where people might not see them. I wanted something like the Bat-Signal to alert people to my work in the area. A searchlight in the sky was not in the cards, so the pavement became the logical choice. For a while I tried the sidewalk, but the street was more intriguing to me. I like staring at the street surface, especially at night. It has a very 3D effect, like you are seeing many layers and depths at once. It made for a very compelling canvas to work with. I was also very attracted to the time element of art that is randomly manipulated by its environment. The ever-changing images created in this way are fascinating to me. I think my approach to using the street as a medium was very different from the concept that the Toynbee Tiler had in mind. Without getting too much into his intentions, which I don’t claim to know, his art is very much based in a specific set of ideas spelled out in a very clear style.

SD: You seem to be a creature of habit, often returning to spots where you’ve placed work before to install new pieces. Why is that important to you?

The artist: Over the years I have been attracted to iconic spots from the industrial past that were adopted by many artists. The old South Street bridge, the Candy Factory in Soho, the old breweries in Northern Liberties and many others. They had layers and layers of art and provided an ever-changing canvas to work with. Most of them are gone now. I still like to use surfaces that have character and interesting features. I get to new locations all of the time, but as I walk so many miles every year, I pass by many locations more than once.

SD: Have you ever collaborated with another artist? Is there anyone you’d like to collaborate with?

The artist: I have collaborated with a countless number of dead artists—I enjoy working with the artistic figures of art history. I have collaborated with contemporary artists like Darkclouds, El Celso, EKG, Art In Ad Places, and many others. I don’t want to leave anyone out, so let’s just say that I have done that. I would like to do something with REVS someday. I collaborate on the street with people all of the time. Most recently with Dee Dee, Sara Lynn Leo, CRKSHNK, and blackligma among others.

SD: What’s the largest piece you’ve ever installed on the street?

The artist: The largest piece on the street was outside of Woodward Gallery on Eldridge Street in New York City. You can find a photo of it on their website. It was maybe five feet tall by sixteen feet wide. Producing big art has never been an interest of mine.

SD: How do you feel about people who remove your works from the street?

The artist: I feel that people who remove my installations from the street do not understand the art that they are looking at. The placement in the urban environment is as important an element of the artwork as the artifact that is placed there. Separating part of the composition destroys the work of art. If you break a toe off of Rodin’s Thinker and take it home, all you have is a piece of metal sitting on your shelf. Poaching of the pieces does cause me to take extra measures to interrupt the removal process and it does cause extra work for me. I do use harsh glues and varnishes which ensure that the artifact is in no way archival and the paper will slowly deteriorate and the colors will yellow over time. It is best to leave it where you find it, and if you are compelled to have the artwork, then photograph it. Your interpretation of the scene will be a more significant work of art than some piece of gunked up paper. I have over the years seen many interpretations of my work that were truly inspired and delivered the work to a new level, and I wish that kind of creative experience to all of my viewers.

SD: How do you approach gallery works differently from street art works?

The artist: Street art works are like the live performance of a musician. Gallery works are like an album of recorded songs. Both elements have an important place in my body of work. I recently completed a series of sculptures for Works On Paper Gallery that relate to my work on the street but would be impossible to realize in a street setting. The original source material for the sculpture was a series of installations that were made from IBM computer punch cards back in 2013.

SD: What’s been the most challenging or surprising part of your creative journey?

The artist: All of it has been a challenge. Being an artist mostly involves solving problems. Being an improvisational artist means solving problems on the fly. All of that feeds my creative being.

SD: Over the years, digital tools have proliferated, and in turn, you’ve availed yourself of them in much of your work. How has the advancement of technology influenced your creativity and your designs?

The artist: I have been working with digital art for 25 years and it has been critical to many elements of my work. To me it is just one more tool in the artist’s toolbox. When I first started digitally manipulating images, there were not any really good digital cameras, so I converted my negatives to disk and CDs. The programs for editing images were primitive by today’s standards and the programs did not handle very large files, so the output images were kind of small. That said, I was always happy with the work I was able to create, and I was able to grow with the tech advances as they came along. I am far from a master of digital design, but I think I use the tools in a way that allows me to represent my ideas in imaginative and varied ways. It is always a source of discovery for me and I am frequently on the receiving end of happy accidents that reveal some transcendent images. Also, I can’t say enough about not having to lug a heavy camera and film rolls around while I am working on the street. That has freed me to work more spontaneously and frees me to interact with a high level of improvisation with the urban landscape.

SD: I’d love to hear your thoughts on some of your recent bodies of work. Can you tell me about the creation of:

- the “distortion” series

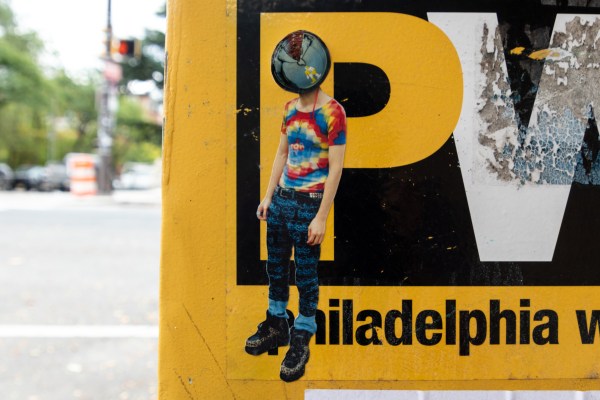

The artist: I have long been intrigued by a round frame of reference for art to be placed in. I think this fascination started at a Pink Floyd concert where a round movie screen was prominent in their visual presentation. For many of my bubbles and round canvases, I start by creating a painting on a square or rectangle. I then isolate a section of the painting and manipulate the image into a circle or a distorted banner. - the “bubblehead” series

The artist: The bubblehead series was conceived while working on the street. I found a paper installation by someone that had the head ripped off, so I glued one of my paper bubbles where the head should have been. I really liked the result, so I started experimenting with the concept of hiding the identity of the figure by replacing a critical element of identity with a bubble. - the “glass bubble” series

The artist: The glass bubbles were the result of a long-held goal in my work. I have, in the past, used painted mirrors to draw the surroundings into the installations. I was working with round compositions and they morphed into the distended paper bubbles. That idea led me to experimenting with glass cabochons and that led to the aha moment of seeing that they had the power to bring a fisheye image of the street into the image in the bubble. I want these works to contain not just the image that I am installing. The placement of my pieces is often carefully selected to fit into their location (my canvas, if you will) so the background is very important to the composition. Many times, the bubbles create a fisheye image of the surrounding street superimposed onto or within the bubble image. This creates an extra dimension to the work. It brings the street into the work. It can even create movement within the piece if, say, a car rolls down the street or a person walks by. It is important to understand the process at work here—it is something I have been striving to accomplish for a long time.

SD: After nearly three decades, you must have had some run-ins with other street artists, or perhaps the authorities, while installing. Do any moments particularly stick (pun not intended) in your mind?

The artist: I have had many interesting encounters with various people on the street. One of my most memorable was while working on the Bowery, where there are always colorful characters around. I had just glued a wooden plaque to a wall and I stepped back a few feet to get ready to photograph it. At that moment, this poor, disheveled man in bare feet and and his shirt hanging half off walked around the corner and stopped next to the stikman and gazed at it a while. He then reached his hand toward it and I thought oh no, he’s going to pull it down. I had seen street people remove and rip up my work many times in the past and I intervened this time by saying please don’t pull that down. By this time he had placed his hand flat on it and turned to me and said I’m not pulling it down, I’m saying a prayer with it. He bowed his head for a few moments and then walked away down the street.

One highlight would be working with Marc and Sarah Schiller on their 11 Spring Street project [in New York]. That event hit at a moment when street art was celebrating a peak in its power. Rubbing shoulders with many of the other great artists of that time was exhilarating and challenging and magical in its energy to create a living visual organism in and on that building. I am honored to have been a part of it from the beginning.

Another highlight was my work being one of the frames of Kodak’s celebrated last roll of Kodachrome film, which was shot by Steve McCurry. I am always conscious of the fact that when I create a work and release it into the world I can never predict what its future will bring, and that piece is a good example of that reality.

SD: Do you have anything planned for your 30th anniversary in 2022?

The artist: I do not have a plan to do any 30th year exhibits. I did two 20th anniversary shows; one in Brooklyn and one in Philadelphia, and that was very satisfying. Nobody seems to be demanding such events this time around. I marked the 25th year with a series of 25 images trapped inside of enclosures which I spread out over the entire year so maybe I’ll do something like that again.

SD: It’s rumored that you’re looking to pass the stikman project on to someone—potentially one of your children. Is that true? If so, why is it important to you that stikman transcend your career?

The artist: I do not have any plan to extend this project beyond my life cycle. In fact, if I lost interest in it at any point in time, I would stop doing it. That said, the consciousness of stikman is floating around the world, so maybe he would enter someone else. Like the spirit of the Dali Lama entering the next one.

SD: What does stikman represent to you today? Is he still, as you wrote in 2005, ‘the absence of personality in art; the little being with no stable form; the unknowable consciousness; the disconnect that most viewers of street art feel with the perpetrators of the artwork’? Or has he transformed yet again into something else?

The artist: That still works for me today, but there is an ever-shifting conceptual basis going on in my brain slamming many other ideas into the mix. I don’t have words that can communicate the feeling I get when I step onto a street and the energy there floods into my being. My hope is that viewers of my work can experience some of that energy.

SD: What’s your take-out order at Tattooed Mom?

The artist: The Pickled Fried Chicken Combo (hold the onion sauce and the cherry peppers) and Waffle Fries.

Many thanks to the artist for agreeing to this interview. It was wonderful to pick your brain and hear about your work straight from the source. Thank you also to our intermediary—you know who you are. We couldn’t have done this without you.

Editor’s Note (from Conrad): Y’all, if you’ve liked this series, I ask you to do one thing this winter. And that’s to order food to go as many times a month as you can from our incredible sponsor Tattooed Mom. As you heard in my Streets Dept Podcast interview with Mom’s owner Robert Perry earlier this year, this place holds such a special place in my heart and in the hearts of many Philadelphians. This is an unimaginably tough time for our restaurant community, so if you have the means please show your support! Thank you.

Read past articles from our Philly Street Art Interviews series by clicking the artist’s name… Season 1: Hope Hummingbird, FaithsFunnn, Bob Will Reign, Taped Off TV, Low Level, Void Skulls… Season 2: Kid Hazo, Under Water Pirates, Symone Salib, SEPER, Morg, Lace In The Moon… Season 3: As Above So Below, Hysterical Men, Reed Bmore, El Toro, JesPaints!

Leave a comment